Bet You Haven’t Heard of This One!

Colorado is known for many things: the mountains, great hiking, river rafting, and skiing, to name a few. In the true crime world, though, most folks have heard of the Colorado Cannibal in reference to Alfred Packer. And his choice to “guide” some early settlers through the Rockies from Bingham Canyon, Utah, to Breckenridge, Colorado. Packer ended up being the lone survivor. Who may or may not have eaten some of the five folks in his party in the winter of 1885-1886? If he did, then it was solely, for survival. After his time in Colorado’s Territorial Prison, he became a vegetarian.

What if I told you there was someone in Colorado’s early history that would give Alfred Packer a run for his money?

The fellow I’m going to tell you about was a real piece of work, that’s for sure. But before I get into his story, I want to let all the Grim folks know. I will also give bits and pieces of other aspects of history and/or historical moments. To further illustrate just who this man was and what life was like back then.

The grizzly crimes occurred in the winter of 1907 and early 1908. When the young state of Colorado was still the Wild West. A few things to remember vigilante justice still happened, and life was very different than it is today in 2022.

One more side note. Y’all are going to see a lot of different spellings of both Antone’s birth name and his aliases in the newsprint. For clarity, I will try to stick with what is believed to be his real name. Full disclosure, though; I’m not absolutely certain even this is correct. Clearly, in yesteryear, reporters figured close was good enough.

Antone Neroni was born in Italy in 1877. There is very little known of his early life, who his family was, or what life was like for him there. What we do know is that Mr. Neroni claimed his first murder was committed when he was twelve. The victim was Antone’s next-door neighbor, a gardener who chastised Neroni. Antone stabbed him nine times in the chest when he caught him sleeping one afternoon. For this, Antone served a ten-year sentence in an Italian prison.

Antone was released when he was twenty-two, around 1899. He was then drafted into the Italian Army. The Boxer Rebellion War was happening about this time, but my sources don’t give any exact specifics for his service. This is a generalization. While serving, Antone again resorted to violence. Having gotten into an argument with his captain, he grabbed a mess hall knife and sliced the captain’s face from his forehead down to his jawline. For this, Antone was sentenced to ten months in a military prison.

After serving his time, Antone was again released from prison. Any guesses about what he did once he got out? Yeah, he stabbed another man, and this time he was sentenced to five months in a “state” prison.

Y’all have heard of repeat offenders, right? What about broken records? Our guy Antone is the latter. After he was released for the third time, he stabbed yet another man, this one in Rome. This time, though, he didn’t stick around to find out if the man had lived or died. He fled to the United States.

Around 1904, Antone was working in Walsenburg, Colorado, and living near Trinidad, Colorado. He had found a job at the Cokedale Coke Ovens for Colorado Fuel and Iron, or CF & I Steel.

Before we get back to Antone’s timeline, I think we need to understand what exactly he was doing at this time for work. At this point in Colorado’s history, the Trans Union Continental Railroad was still under construction out here in the Wild West. In order to make the rails for the trains to ride on, the coal had to be turned into coke to fuel the iron smelters.

If y’all are like me, this doesn’t make much sense, so let’s clarify a bit further. Turning the coal into coke required a process of removing as many impurities as possible from the coal. Then heating the coal with as little air (oxygen) as possible. This is an oversimplification of the process; nonetheless, the result was a hard, gray, porous fuel called coke. The coke was needed to make the iron smelters, hot enough to form (cast) the train rails.

This is so we modern folk can understand this was hard, physical work. It was extremely dirty and done in a temperate desert climate. Brutal, just plain brutal work.

One more thing to clarify before we get back to Antone’s timeline: his living situation at this time, no doubt he was living in a company town. Allow me to give a little background on what exactly this company town means, as it will explain a lot about the next notable moment in Antone’s history.

These company towns generated a vicious cycle for most workers and their families. The company would tell workers they would provide a place to live (often in dismal conditions). There would be a company store nearby and a grocery and butcher shop within the town. This all sounds good, right? Most folks didn’t even have a horse or any other means of transportation. This was a great selling point for people in these lines of work.

But and you know there is a big but here. What they didn’t tell the workers is that their pay would be in vouchers, not cash. The company set the prices for rent, groceries, and equipment merchandise. And it could raise these as it saw fit and at any time. It was common practice to “have to” borrow against your next voucher. It was extremely difficult to be able to save up money in these company towns. So, you know there was corruption taking advantage of corruption. These company towns were more akin to indentured servitude.

Now, let’s get back to our guy Antone’s story. He was working at the coke ovens and living in a company town. Antone was really working for his money. He was becoming frustrated at not being able to cash out his vouchers. In fact, his boss was behind on quite a few of his voucher payments. Antone decided enough was enough, and he told his boss he wanted his money.

The boss tried to give him a run around; clearly, this boss didn’t know who he was dealing with! Antone, for once, didn’t immediately jump to violence. He decided to give his boss one last chance. Antone threatened the boss’s wife and family if he didn’t get his back pay within the next twenty-four hours. By the newsprint dropping this conflict here, Antone moving from Colorado to Illinois. I’m guessing his threat of violence worked? And there weren’t any additional murders at this point.

I couldn’t find any news articles online from Antone Neroni’s time in Illinois. It appears he came back to Colorado in 1907. At this point, Antone was thirty-one years old and moved to Florence, Colorado, where he bought a farm/ranch. He was then going by the name Tony Bavari. This is where our true crime story is about to take off.

Neroni worked at a “truck garden” on River Road in Florence. Keep in mind this was a different time. Automobiles were still in their infancy, and grocery stores were not as common as they are today. To be a truck farmer meant that Neroni worked on a farm and would haul his produce to be sold out of a large cart or “truck cart.” He would harvest the produce on the farm and then move it by a horse-drawn cart into town to sell. Neroni worked with Joseph Minichello and his brother Dominick Minichello on the truck farm.

Neroni had hired a housekeeper, a young Mrs. Frank Palmetto. She had been working for him (and others at the farm) for a few months. Her employment had caused a good deal of strife in her marriage. Why, you ask? Antone fancied Antonetta Palmetto, and he wasn’t too shy with his advances. Mrs. Palmetto’s husband, Frank, wasn’t having any of this, so he divorced her and left Florence for New York. Well, this left Antonetta in quite a pickle! She continued her employment with Neroni, but she didn’t feel the same way about his advances. Then she disappeared, in December 1907, by some reports. Mrs. Palmetto had been living with Dominick and Joseph in their home, throughout her employment with all the farm workers.

There was another worker at the farm, an elderly fellow named Ercola Buffetti. I couldn’t find much information on him. Other than he had been in Florence a while and was respected and considered a consistent worker. He was said to be in his sixties or seventies at the time of his disappearance in December 1907.

For the next two disappearances, I couldn’t find definitive documentation as to their order. Some of the newspaper clippings did state that both brothers disappeared on the same day. I’m going to go with this since it would make sense, kind of. Here goes: What we know for certain is that there was an argument with Joseph Minichello on January 6, 1908. Then both brothers, Joseph and Dominick Minichello, disappeared.

The next morning Mrs. Joseph Minichello, with her two young daughters in tow, wanted to go to town, to report her husband’s disappearance to the police. As she was headed out, though, she encountered Antone. He tried to coerce her into his cabin. Under the guise that he would hook up the horse and buggy for her trip to town. She didn’t trust Antone, so she and her daughters declined his offer and went about walking into town. She knew something was wrong on the farm, and she was extremely suspicious about why her husband hadn’t returned home last night after his intense argument with Neroni.

Mrs. Minichello made her way to the police in Florence and filed her complaint against Antone Neroni. She told the police about the argument between her husband and Neroni. Also, her husband hadn’t come home last night, and about the three other disappearances from the farm. And she finished by telling the police.

“I believe Tony Bavari (aka Antone Neroni) killed my husband on that night.”

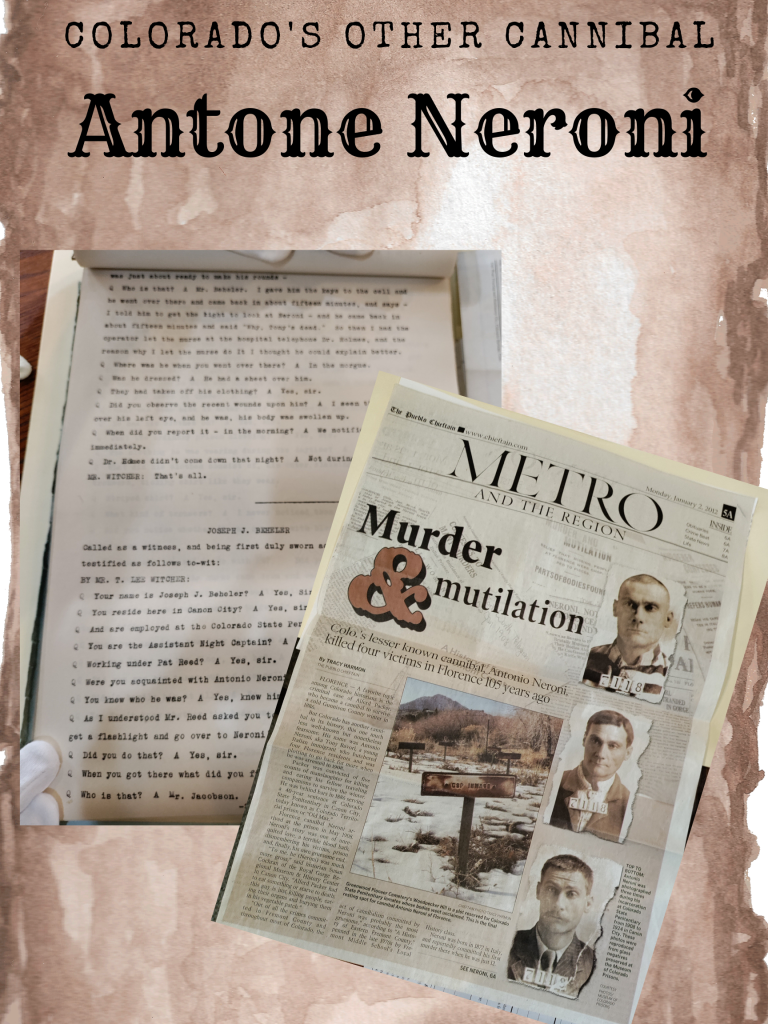

The Sunday Oregonian, from Portland Oregon on January 12, 1908.

It was after this point that Antone Neroni was questioned and then taken into custody by the police. When Neroni was searched, it was found he had $350, and one of the bills had a stain the police believed to be blood. He also had a gold ring.

The police in Florence began investigating the possibility of a crime or crimes and seeking out anyone who might have had any interactions with Neroni. Neroni’s cabin was searched, and charred human remains were found in the adjoining cabin to his. Later, it was found that this was the residence of Ercola Buffetti, one of the missing men.

In Neroni’s cabin, there were bundles of letters, including one from his father, that was addressed to Tony Neroni. At this time, the police realized this must have been Tony Bavari’s real name. They also found that Neroni’s family had come into an inheritance. His father was telling Antone he would help clear his name of the murderer back in Italy. If Antone could make his way back to Italy. (I guess the last man he stabbed in Rome had died after all.) The police also found a bloody knife in the cabin and a bloody axe outside his cabin. There was an area out in the orchard of the farm where they found signs of a struggle, but no bodies . . . yet.

Next, the police found Ms. Nasiro Sisinorzo, a Mexican woman who told them she had been asked to wash and mend some of Antone Neroni’s clothes. There was a shirt that was torn and had stains that she believed might have been blood.

Police Chief Edward Furniss tried to get Neroni to talk about the four missing people. Finally, when the topic arose of Mrs. Palmetto, who was only eighteen years old at the time. Neroni stated that he knew where she could be found, but she wouldn’t be alive. At this point, he also confessed to having killed his neighbor back in Italy.

Chief Furniss and his deputies had a running theory about Antone’s crimes. They believed at this time that Nernoi was planning to return to Italy. To do this, he killed the Minichiello brothers to get them out of the way. Then he would dispose of their joint property. In order to get as much money as he could. Dominick Minichiello had $200 when he disappeared.

Originally, Antone Neroni was taken to the Florence jail, after his arrest, but he didn’t stay there for long. Mobs of angry Italian workers from the coal mine camps were planning to storm the jail. To commit some gratuitous violence. And perform a bit of vigilante justice in the form of a lynching Neroni. Word of this plan reached the Florence jail, and a quick plan was made to move Neroni to Cañon City. He was smuggled in a closed carriage under a heavily armed guard to the Denver & Rio Grande Depot at 1:15 PM to be placed on the 1:30 PM train to Cañon City. The prisoner was surrounded by over a dozen guards armed with revolvers and rifles in two carriages.

The crowds of angry Italian workers began gathering after news from a physician confirmed that the pieces of flesh gathered from along the banks of the Arkansas River near Neroni’s home were, in fact, human remains. The items recovered so far, were a base of a tongue, lungs, and a part of a human torso. At this same time, there were over fifty men searching up and down both banks of the treacherous river, looking for any other remains. Towns south of Florence were advised to be looking for more as the river currents would have likely moved remains downstream. If any should be found, Florence law enforcement and the Fremont County coroner wanted to be advised.

The police continued to search for the bodies of the four missing people. A week after taking Neroni into custody, there still weren’t any bodies found.

Neroni had to be moved again due to the mobs that were gathering in Cañon City. This time, Neroni was taken to the Pueblo County jail. Under the cover of night, He was transported in a carriage from the jail to the Santa Fe railroad station. There wasn’t anywhere safe to house Neroni in Fremont County while he waited for his trial in May.

It was time for a change in tactics. Since Neroni wasn’t talking, some of the officers in Cañon City and Pueblo devised a plan to “plant” one of their own in the cell with Neroni. Detective Frank Sedesky was “undercover” as Peter Angelo, a member of the Black Hand Society. It took a day or so of “Peter” chatting with Neroni in Italian to get the fiend to talk. Peter had told Neroni he was a member of the Black Hand. He was being held for his thirteenth murder out of Omaha, Nebraska. He also produced a newspaper clipping from Pittsburg, Pennsylvania (this was a fake and part of the ruse). About the Black Hand’s work there. Then Peter told Neroni he could join the Black Hand if he had killed a dozen people or more. If he had, then the Black Hand would break them both out of jail.

Neroni said he had killed eight people in Italy and four in Florence. So, Peter asked for details, a way to verify these last four since Neroni had been charged, but there weren’t any bodies as proof. The two continued to talk back and forth before Neroni and Peter made devilish plans.

Neroni relayed how he had buried three of the bodies close together and had planned to blame those murders on Joseph Minichiello, whom he had buried elsewhere. Neroni was going to say that Joseph had run off after murdering the other three.

He also told Peter that he had planned to kill Joseph’s wife and daughters the next day. That is, if the wife had, she would have gone for his ruse and waited in his cabin, so that he could get the carriage ready to take her and the children to town. His plan was to kill Mrs. Minichiello with the axe, then boil up the children to drink their blood. He told Peter that the little ones produced too much blood to be dismembered and buried. This was okay with him, though, as he liked the taste of blood.

Peter suggested Neroni should show the cops where Annonetta, Ercola, and Dominick were buried. Then, break away from them and finish off Joseph’s family. This would get Neroni to the number of murders needed for the Black Hand to break him out. Unknown to Neroni, Peter had already relayed his confession to other Pueblo deputies. Neroni was buying into the ruse, hook, line, and sinker. Antone made arrangements with the Pueblo sheriff to show the Florence Police Chief Esser where three of the bodies were buried.

Antone Neroni was returned to Florence and kept under close guard. He was also taken back to the ranch where he and all the victims lived. He clammed up until the police put a noose around his neck while he was still shackled and threatened to let the mobs string him up. Don’t you know, Antone suddenly found his voice. And showed the police where Annonette, Ercola, and Dominick’s dismembered remains were buried. The police and the coroner were all surprised by how well the bodies had been preserved for the last three to four months.

Let’s take a minute to talk briefly about the Black Hand Society. At first, reading through the various newspapers, I didn’t realize this was a real thing happening at the time. I honestly thought it was part of the ruse to get Neroni to confess. Oops! I was wrong.

The Black Hand Society

La Mano Nera is the way of saying the Black Hand in Italian. No matter the language, the mere mention of the Black Hand would instill such fear in early Sicilian and Italian Americans that they would cross themselves. La Mano Nera wasn’t technically affiliated with organized crime; it was around before the mafia’s rise to fame. The Black Hand Society was active from 1860 through 1920. The way they operated was to send extortion or blackmail notes to merchants and “well-off” people in Italian communities across the United States. The notes would include symbols of a black hand, knives, and other scare tactics. These notes had threats of business destruction from things like fire or the potential harm or murder of the person being extorted or their loved ones.

The Black Hand Society declined around 1920, when two significant things happened. The first was the rise of big-money bootlegging during Prohibition. The second was the arrest and trial in Manhattan’s Little Italy of Il Lupo (the Wolf) whose actual name was Ignazio Saietta. Mr. Saietta was apprehended by federal authorities and sent to prison for thirty years for counterfeiting. The Wolf was considered the head of the Black Hand Society.

On a side note, I think the two things that had a direct effect on the Black Hand Society in 1920 are very interesting. My brain wants to scream, “Mafia! Capone!! Elliott Ness!!” But I don’t have any research to validate these allegations. Is this just a serendipitous coincidence?

From Cañon City Back To Pueblo

The police in Florence moved Neroni to the county jail in Cañon City to keep the miners from lynching him. This wasn’t far enough, though. Since the three bodies had finally been found and the miners weren’t buying the story that Joe Minichiello was the murderer, again, the cannibal had to be moved so he could be tried for the four murders.

I couldn’t nail down the specific date of this move, but according to the various newspapers, it occurred around the last week of January 1908 or the first week of February 1908. This time, it seems Antone was taken by horse-drawn covered wagons to the Santa Fe railroad line in Cañon City. Then, while on the train and when it passed by Florence, the escorts covered all the windows to ensure he couldn’t be seen. And they did this at night!

Neroni Taken To Pueblo

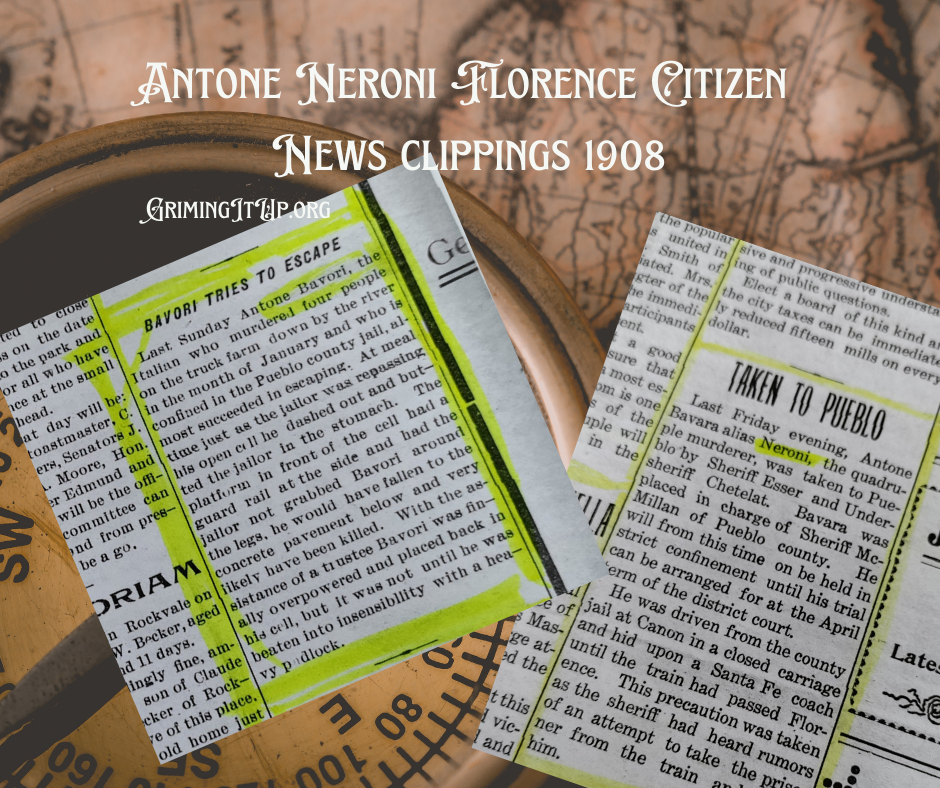

On March 2, 1908, Antone’s jail cell door was accidentally left open, and he wanted to escape the Pueblo jail. When the jailer, W. E. Ward, was walking past on his rounds, Neroni saw his chance. He readied himself by standing, and when he heard the jailer approaching, he leaned forward and ran at the man. Neroni’s plan was to knock Officer Ward against the wall and then throw him from the third-floor tier over the railing. He believed that the twenty-foot fall would kill the officer, and Neroni would be able to escape.

Instead, Officer Ward fell to the ground and fought back. Grabbing Neroni by the leg and hurling him to the floor. At this point, a trustee, Warren Smith, came by, grabbed the Italian by the throat, and shoved him back into his cell. In the newspaper clippings above, I guess there was a bit more to getting Neroni back in his cell, but this is the only article that indicates a beating with a padlock was involved; the others left this detail out.

Let’s be real: this was the Wild West, and an officer was almost killed, so I’m sure this isn’t too far-fetched.

His Stories Are Vastly Different

I love how appropriate this headline is for what Neroni did next. He changed his story and was now saying he, himself, witnessed another man’s murder, Joe Minichiello. He told Detective Sedesky that a miner from the Coal Creek mines named Matteo had done it because he wanted to marry Joe’s wife. These police officers weren’t fools, so they went down to the mine camps and found a man named Matteo Lomavario. This miner told the authorities he had met Neroni a few times when he was buying produce in Florence. Turns out Matteo didn’t know Joe’s wife. He denied the allegations and introduced the officers to his own wife. I just have to shake my head at this part. Neroni was definitely showing his desperation.

“The police and sheriffs say this is only a dodge on the part of the prisoner but will not let him know that they disbelieve his story.” Florence Daily Tribune, January 23, 1908.

Joe Minichiello Is Found

After multiple trips from Pueblo to Florence by automobile, Neroni still wouldn’t tell authorities where Joe was buried. From his confession to Detective Sedesky, Neroni had indicated Joe was buried away from the hog pen where the other three bodies had been dug up. One fateful afternoon, Mr. Roy Green leaned up against a fence post by the orchard on Neroni’s farm. After days of digging here and there. He was tired, just like all the other men who had been helping to uncover Neroni’s devilish deeds. Mr. Green happened to look down and noticed an area close by where the earth looked recently disturbed. He started digging, and Joe was finally found.

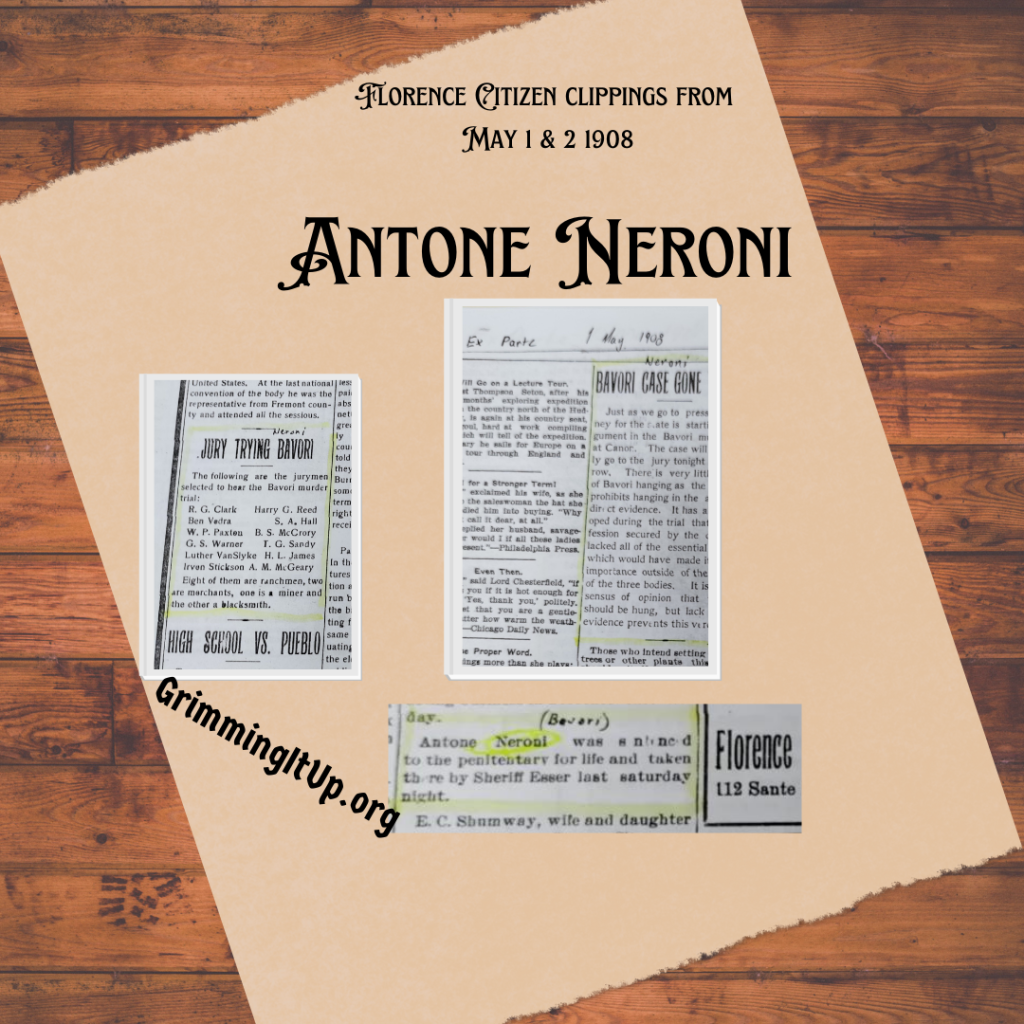

On May 1, 1908, Antone Neroni had his day in court for his murders. His jury had been selected and consisted of all men, two merchants, a miner, a blacksmith, and eight ranchmen. This was before the jury secrecy stuff we’re used to today. It was quite the town news and an honor to be on a jury, so of course, all the jurors’ names were published in the paper. R. G. Clark, Ben Vedra, W. P. Paxton, G. S. Warner, Luther VanSlyke, Irvan Stickson, A. M. McGeary, H. L. James, T. G. Sandy, Harry G. Reed. S. A. Hall, and B. S. McCrory.

During the trial, it was discovered that Neroni had given a false timeline for the disappearance of Mrs. Palmetto. He stated that she disappeared around November 10. When he was questioned about her being gone, he said she went to Pueblo.

It turns out that a witness happened to be Neroni’s next-door neighbor in Florence. Joseph Milner, who was also a truck farmer, testified that he had overheard an argument between Neroni and Mrs. Palmetto. Mr. Milner had heard Neroni threaten to kill Mrs. Palmetto. Shortly after this, she disappeared.

It turns out when the police recovered her body that, her throat was slit. She was the first to go missing, having disappeared on September 26, 1907. The next victim Neroni murdered was Mr. Buffetti on December 27, 1907. He had killed Mr. Buffetti in his adjoining cabin by splitting his head with an axe. Then dismembered him and tried to burn some of his limbs. From all of the newspaper clippings, I could find at this point. None of them specify what Dominick’s cause of death was, only that he was also dismembered. It is believed that Dominic was murdered on December 28, 1907.

This leaves us with Joseph Minichiello’s murder that occurred on January 6, 1908. It is presumed that Neroni snuck up on him and began to stab him, and, as Joe went down to the ground in the orchard, Neroni continued to stab him four more times for a total of five wounds in the neck and right shoulder area.

Joseph’s body was the only one that wasn’t dismembered. What the authorities did find was a bucket that had been filled with blood, and buried with Joseph’s body. The police and prosecutor believed that Neroni had stabbed Joseph and collected the blood in the bucket before getting his cart to haul Joseph from where he had murdered him in the orchard. He then took the corpse through the river, back upstream to bring it back down to the same basic vicinity to bury it. Neroni was trying to suggest that the body had been thrown into the river if anyone should come looking.

During the trial, some other interesting things came out. For instance, the neighbor, Joseph Milner, told the judge and jury about a conversation he had with Neroni after Joseph Minichiello’s disappearance. Mr. Milner told Neroni that it didn’t look good for him with folks up and missing. Next, Mr. Milner stated that Neroni turned a bit pale and rambled on about how he would sell everything and return to Italy.

Mrs. Joe Minichiello stated that the gold ring found in Neroni’s pocket was her husband’s wedding band. Neroni’s defense lawyer argued that the ring had belonged to Neroni’s mother.

The state prosecutor delivered his closing arguments to the newspaper account when the reporter left. Even though there had been four murders, it seems as though all were put before the jury in a single case on a single day. Interestingly, Antone wasn’t eligible to be hung since there was no direct evidence in any of the murders. The obtained confession lacked corroborating information that would have met the Colorado state law’s requirement for capital punishment or death by hanging. The jurors were instructed to decide the length of Neroni’s sentence up to life imprisonment.

“It is the consensus of opinion

that the fiend should be hung, but lack of direct

evidence prevents this verdict.”

Florence Citizen News Paper May 1, 1908

On May 2, 1908, Antone Neroni, aka Tony Bavari was sentenced to life in prison. Then officially transferred by Sherriff Esser to Colorado Territorial Prison in Cañon City.

I bet y’all thought this was the end of the story, didn’t you? Yeah, no! This guy, Neroni, wasn’t a model prisoner. He, too, would come to a sad end. He would also cause more problems after his death for a prison guard, the warden, and the deputy warden. This fellow just exuded bad karma. However, while in prison, Neroni learned English from a Catholic priest. This same priest even stated how Neroni was a changed man during Neroni’s 1917 appeal to the Colorado governor. Neroni lost the appeal. Big shocker, right?

I’m guessing, though, that the priest was looking past the fights Neroni got into with other inmates. And how sometimes, in these fights, Neroni would bite chunks of flesh from the other inmates. On September 12, 1911, he was written up for fighting in the workhouse. On February 15, 1918, he viciously assaulted Inmate No.9145 by striking him in the head with a shovel. There were more incidents documented in the nineteen years before his own murder.

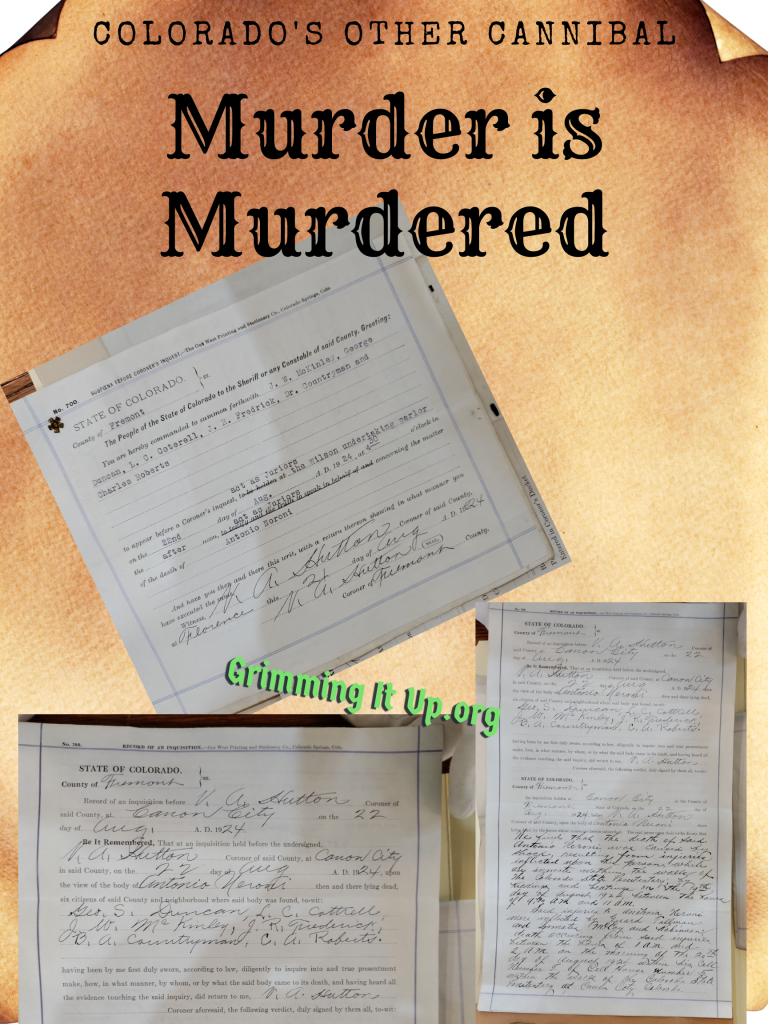

On August 20, 1924, Neroni was beaten severely in his cell by two inmates, Jack Robinson and W. P. McCoy, and a guard, James Tillman, then left to suffer his injuries till it was certain he was beyond help. Tillman alleged that Neroni had a knife and that the two inmates were happening by and saw a struggle between Neroni and himself, and then intervened to assist the guard. However, during the coroner’s inquest, both inmates stated there was no knife. They also stated that Tillman didn’t want either of them to stop beating Neroni till he was dead.

Neither of the inmates had any additional charges from Neroni’s beating and eventual death. Tillman was charged and convicted of assault. Resulting in a six-month sentence in the county jail. Now, we will end this with a short article from the Iowa City Press Citizen Newspaper printed on January 5, 1925:

“William E. Sweet, as governor and complement today filed with the symbols are as Commission charges against Thomas J. Tynan, warden of the Colorado State Penitentiary and nationally known, and George Buchanan, deputy warden, asking removal of both officials. The charges accused Warden Tynan of permitting prisoners to be shackled and flogged and otherwise abused; of having been absent from duty for periods ranging from one to three weeks; and of intemperate habits, and of being generally unfit for his post as warden of the prison.” Six charges were laid against Deputy Warden Buchanan.

One paragraph of the charges against Buchanan read, “. . . because of the incompetence and the inefficient management of said penitentiary under said George Buchanan, as deputy warden, Antonio Neroni, an inmate of the said penitentiary, was recently assaulted and murdered, and after the said Antonio Neroni had been so assaulted and was suffering from mortal wounds which had been inflicted upon him, the said George Buchanan, being then and there in the charge of the said penitentiary as such deputy warden wholly neglected and refused to provide said Antonio Neroni with medical aid and assistance and on the contrary permitted the said and Antonio Neroni to be thrown into a cell and there to linger and die.”

Thank you for spending time with us today. We appreciate each and every one of you!

If you want to continue reading, we have several other true crime stories you might like, such as True Crime Lover’s Guide to Forensic DNA. Here is another Colorado serial killer that was finally caught after thirty-four years, Denver Hammer Killer.

Sources:

All news articles, pictures, and/or videos are used under the Fair Use Act, and individual sources are given credit.

https://chicagology.com/notorious-chicago/1910blackhand/

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Black-Hand-American-criminal-organization

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Colorado_Fuel_and_Iron

Museums

I would like to give credit also to the museums that housed different parts of the newspaper articles and other documents that made this post possible. Both the staff of the Florence Pioneer Museum and the Royal Gorge Museum were immensely helpful. I can’t say enough about all these folks for their assistance in helping me to put this together. Thank you!

A huge source for this post is in thanks to the Florence Pioneer Museum! They provided numerous Florence Citizen newspaper articles. I can’t give each article citations for specific dates of printing or volume. Since these were cut out of original newspaper posts without citation credits.

The Royal Gorge Museum was vital to getting newspaper articles from the Cañon City Daily Record and the Fremont County Coroner’s Inquest.

Lastly, I would like to thank my editor Donna Marie West. She also has a Facebook page y’all can reach her at. I have to say she is an absolute lifesaver and easy to work with. Thank you, Donna!